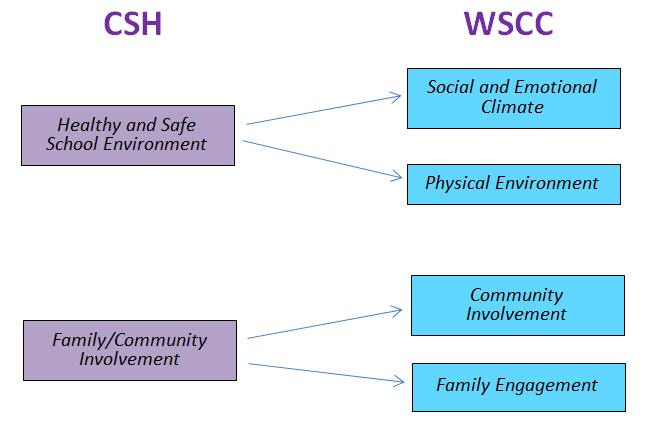

Let's turn our attention to the Healthy and Safe School Environment aspect of the CSHP which corresponds to Social and Emotional Climate and the Physical Environment tenets of the WSCC.

Let's turn our attention to the Healthy and Safe School Environment aspect of the CSHP which corresponds to Social and Emotional Climate and the Physical Environment tenets of the WSCC.

According to the World Health Organization’s INFORMATION SERIES ON SCHOOL HEALTH, DOCUMENT 2, The Physical School Environment: An Essential Component of a Health-Promoting School, "Environmental challenges and opportunities vary considerably among schools around the world, across countries and within communities. Similarly, the resources available to schools to manage health hazards vary as widely as the threats themselves, often creating formidable management challenges, particularly in the poorest parts of the world." “The children of today are the adults of tomorrow. They deserve to inherit a safer and healthier world. There is no task more important than safeguarding their environment.” This message is emphasized by the Healthy Environments for Children Alliance (HECA), which focuses attention on the school environment as one of the key settings for promoting children’s environmental health. "The extent to which each nation’s schools provide a safe and healthy physical environment plays a significant role in determining whether the next generation is educated and healthy. Effective school health programs, including a safe and healthy school environment, are viable means to simultaneously address the inseparable goals of Health for All and Education for All."1

The physical school environment encompasses the school building and all its contents including physical structures, infrastructure, furniture, and the use and presence of chemicals and biological agents; the site on which a school is located; and the surrounding environment including the air, water, and materials with which children may come into contact, as well as nearby land uses, roadways and other hazards. If children are the seeds of our future then schools are the garden in which the aspects of a healthy environment are the micronutrients plants need to reach their full potential. Take crucial nutrients out of soil and the land becomes fallow. In the same way that fertile fields enable healthy plants to take root and reach for the sun, a healthy learning environment can empower individuals to seek out their path to enlightenment.

WHO defines a health-promoting school as “one that constantly strengthens its capacity as a healthy setting for living, learning and working.” The American Academy of Pediatrics defines a “healthful school environment” as “one that protects students and staff against immediate injury or disease and promotes prevention activities and attitudes against known risk factors that might lead to future disease or disability.”2-3

The physical school environment strongly affects adolescent health in myriad ways, including contaminated water supplies causing diarrhea, air pollution worsening acute respiratory infections or triggering asthma attacks and exposure to chemicals, solvents, and pesticides. Furthermore, children, relative to their body weight, breathe more air, consume more food and drink more water than adults. Exposure to contaminants in the air, water or food will consequently be higher than adults. Reduced immunity, immaturity of organs and functions and rapid growth and development can make children more vulnerable to toxic environments. Compounding these risks are behavioral patterns such as lack of hygiene and the lack of experience in risk assessment.

A healthy school environment can directly improve children's health and effective learning and thereby contribute to the development of healthy adults as skilled and productive members of society. Schools also act as an example for the community. Students, school employees, families, and community members should all learn to recognize environmental health threats that may be present in schools and homes. As members of the school community become aware of environmental risks at school they will recognize ways to make home and community environments safer. In addition, students who learn about the link between the environment and health will be able to recognize and reduce health threats in their own homes.4-5

WHO estimates that between 25% and 33% of the global burden of disease can be attributed to environmental risk factors. About 40% of the total burden of disease due to environmental risks falls on children under the age of 5. Respiratory infections are the most common among all diseases in children, and pneumonia is the primary cause of childhood mortality worldwide. Indoor and outdoor air pollution may be to blame for as much as 60% of the global burden of disease brought about by respiratory infections.6-7

Diarrheal diseases, the second most common global illness affecting young children and a major cause of death in lower income countries, are closely linked with poor sanitation, poor hygiene, and lack of access to safe and sufficient supplies of water and food. Each year, nearly two million children under the age of five die of diarrheal diseases caused by unsafe water supplies, sanitation, and hygiene. Interventions such as simple hand washing have been shown to reduce sickness from diarrheal diseases by up to 47%, and could save up to one million lives.8

In high income countries, road traffic injuries are the most common cause of death among children aged 5 to 14, and account for approximately 10% of deaths in this age group. In low and middle income countries they are the fifth leading cause of death in the same age group behind diarrheal diseases, lower respiratory infections, measles and drowning. Schools located near busy roads or water bodies have increased risks of these types of injuries. Falls and injuries within the school grounds can occur as a result of poorly maintained schools or poor construction management.9

Developmental disabilities include a variety of conditions that occur during childhood and cause mental or physical limitations. These disabilities include autism, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, mental retardation, and other neurological impairments. Many researchers believe an epidemic of learning and behavioral disabilities is occurring among children. Developmental disabilities are believed to be a significant and frequently undetected health problem in developing countries.10

Malnutrition and parasitosis (especially helminth infections) may contribute to these illnesses. In India, undernourished rural children 10-12 years of age demonstrated a range of learning deficiencies when compared to normally nourished children. Considering the estimate that a third of the world’s children suffered from malnutrition during the 1990s, the potential for widespread learning deficiencies is staggering. Schools could play an important role in ensuring that students have nutritious food to eat several times per day. Schools that offer a lunch program give children an opportunity for at least one safe and nutritious meal a day. This also serves as a motivation for families to send children to school.10-12

The condition of a school’s physical environment can impact the health of both students and staff. It has been demonstrated that all members of the school community need clean air to breathe, clean water to drink, a safe place for recreation, a safe way to travel to school to avoid accidents, and protection from extreme temperatures and ultraviolet radiation. A safe and healthy physical environment requires a good location and safe buildings; protection from excessive noise; natural light; clean indoor air and water; a healthy outdoor environment; and healthy school-related activities including safe management and maintenance practices, use of non-toxic cleaning supplies, careful use of pesticides, vector control, and use of non-toxic art supplies.

To learn, children and adolescents need to feel safe and supported. Without these conditions, the mind reverts to a focus on survival. Educators in high-performing, high-poverty (HP/HP) schools have long recognized the critical importance of providing a healthy, safe, and supportive classroom and school environment. This means all forms of safety and security while at school—food if hungry, clean clothes if needed, medical attention when necessary, counseling and other family services as required, and most of all caring adults who create an atmosphere of sincere support for the students' well-being and academic success. When students who live in poverty experience comprehensive support that works to mitigate the limiting, sometimes destructive poverty-related forces in their lives, the likelihood for success is greatly enhanced.

Healthy, safe and supportive learning environments enable students, adults and even the school as a system to learn in powerful ways. Every student needs and deserves to feel respected and free from physical harm, intimidation, harassment, and bullying. The learning environment of a school goes beyond the classroom to include safety at bus stops, the playground, lunchroom and even the bathrooms. Matthew Mayer and Dewey Cornell refer to teasing, hateful language, and social exclusion as factors of "low-level incivility that impact a student's adjustment and psychological well being". Through daily vigilance, consistent consequences, and continual monitoring of progress with frequent midcourse corrections by the adults, HP/HP schools wage war on such low-level incivility. Still, leaders of these schools report that the school did not become truly safe until the students came to believe that destructive behaviors would not be tolerated. Only then did they feel comfortable enough to trust each other and to join the adults in collectively working against inappropriate behavior. As a principal of an HP/ HP school on the West Coast explained, "Once the kids let the other kids (particularly new kids) know that we don't do that stuff in our school, it all began to change. They were taking responsibility for their school and liked the way that felt."13

High-performing, high-poverty (HP/HP) schools provide a protective factor when they find ways to ensure that their students living in poverty will be able to participate in extracurricular activities. The importance of such participation to the creation of a bond between students and school has long been known. Whereas middle-class children have opportunities to develop their skills and talents through private lessons and participation in community-based activities in their elementary years, kids who live in poverty generally do not. Poverty poses a variety of barriers to participation for many students, such as the cost of fees, equipment or instruments, uniforms, and transportation home after participation.13

In a recent study of the Chicago public schools, Anthony Bryk, president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, and his colleagues concluded, "Relationships are the lifeblood of activity in a school community" (Bryk, Bender Sebring, Allensworth, Luppescu, & Easton, 2010, p. 137). Their previous work targeted trust as the essential building block in the positive relationships that foster authentic school improvement. He concludes, "In short, relational trust is forged in day-to-day social exchanges. Through their actions, school participants articulate their sense of obligation towards others, and others in turn begin to reciprocate. Trust grows over time through exchanges in which the expectations held by others are validated by actions" (p. 139). This pervasive sense of trust characterizes the relationships found in HP/HP schools among educators, students, families, and other stakeholders.15

Many HP/HP schools engage parents, families, and other community members by opening their doors and expanding their schedules to offer clubs, parent support and education, early childhood activities, GED programs, advisory groups, community education classes, and a host of other events and activities of interest to the community. These HP/HP schools partner with community or city organizations, local foundations, state and municipal agencies, service clubs, universities, and businesses to host these valued endeavors in their buildings, as well as offer services at times that better fit families' work schedules. When the collective community actors are on the same wavelength then anything is possible when it comes to effecting the change they want to see.

In the following blog posts we'll delve deeper into other tenets of CSHP and the Whole Child framework now that we have covered the importance of the physical environment on learning. We don't need to tell seeds how to grow but we do need to provide them the right foundation and nutrients to reach their potential. Every step we take in the right direction is a small victory to that end.